ROLLING ON THE FLOOR, LAUGHING

Collaboration and Friendship

NM = Nisha Madhan / JC = Julia Croft / VF = Virginia Frankovich

NM = Nisha Madhan / JC = Julia Croft / VF = Virginia Frankovich

I trained as an actor in Tāmaki Makaurau and I started out with roles in mainstream theatre and television. As far as an actor-ey career goes, I didn’t do badly, and I still mess around with the mainstream from time to time. I do not devote my life or art to the mainstream however because the mainstream either 1) ignores me 2) makes me work three times harder than everyone else to not be ignored 3) tokenises and exoticises me while expecting me to be grateful for it 4) says things like ‘don’t stir the pot, no one likes a negative nancy, watch that attitude of yours’ or 5) simply misunderstands me for not wanting to talk about where I am from all the time. I am a woman in a world where all the parts, jobs and commissions are for men. I am also a brown person in a world where all the parts, jobs and commissions are for white people. And whether I like it or not, these things always underpin my work.

This is why I choose to make my own work which has turned out to be mostly experimental, live art. I did it because I needed to take matters into my own hands. Cast myself in the roles I wanted to play and create narratives that empowered me to be something other than the cute little Indian girl at the end of the Jungle Book. In my live art world, I can be powerful, chaotic, sexy, dangerous, angry and the centre of plot, rather than the epilogue. My live art world is one that can make your butt clench with its refusal to play into your assumptions of who I am supposed to be or who I am about to become. The glory of this world is that it thrives in intersections and collaborations. It allowed me to attract other artists who, like me, struggle under the hurtful, ignorant eyes of the mainstream, particularly in the sexist and racist settings of theatre in Aotearoa.

Of those artists the most explosive collaboration has been with my friend, Julia Croft. We make work that is non-linear, often messy, feminist, subversive, uncertain and asks more questions than it gives answers. I like making this kind of work with Julia because I can relate to living a life that feels non-linear, often messy, feminist, subversive, uncertain and full of asking more questions than I can get the answers to. The more I live this life, the less inclined I am to find spaces or people that are linear, clean, misogynistic, mainstream, certain and sure of what the answers are. Spaces and people like this annoy me. While I can understand the attraction of feeling in control, I like feeling out of control, myself. When I experience a performance with that knife-edge quality of being uncontrolled, I feel like the outside world lines up with what’s going on inside of me. Like a rollercoaster for someone who is already on a rollercoaster.

Julia and I make work that is about finding power structures and tearing them down. The theatre is our starting point, then, the idea of us in relation to (or in conversation with) the audience. That’s what really gets us going. In our work, the theatre is the theatre, not a lounge room or bus stop although it may, at times, feel like a different world. Julia is Julia, not an 18th Century lady in a big dress running through a forest that we somehow are able to see. You, the audience exist, you are not invisible, or tucked safely behind a fourth wall or a television set, you are with us and we are experiencing the world together.

Our collaboration doesn’t exist with us individually. We work intuitively together and I’m proud of our work as an example of what an intersectional collaboration could feel like. That is to say that it is inextricably bound up and entangled in both of our bodies and timelines. It is practically and emotionally fuelled by our friendship. Practical, because we know how to live around one another having spent many years on the road touring mainstream theatre performances. Emotional because we consider each other’s friendship the primary relationship in our lives. Our art illuminates our friendship while our friendship carries our art. It is “how we pick each other up”1 and how we live.

When we began it felt the same. We were two young women fighting the patriarchy together. Over time our differences have entered into our collaboration. I am brown, she is white. I am short, she is tall. I am fat, she is skinny. At their worst, these differences hurt. At their best, they propel us in our personal political agendas to break up and take up space in the world. It is through each other that our dreams take flight further than they would individually. It is through each other that our feet are able to stay planted firmly in the realities of being different. We have co created so many images together, but the real work has been choosing to stay in the room with each other and a blood pact to never leave the other behind.

We began this piece of collaborative writing in 2019, and a version of it was published in Performance Paradigm, Vol 15, Performing Southern Feminisms in 2019. At that time I was in Auckland and Julia was in Perth and we had begun touring two of our works to Australia and Europe. I dropped Julia off at the airport in February of 2020, sending her off to London to perform our latest work, Working On My Night Moves, before she was to move to Glasgow. By March she had returned unexpectedly just before the borders closed, and we found ourselves making our way in the world through art together again. We picked up this piece of writing again in 2021 on the precipice of opening a new work, Terrapolis, another work whose life was unexpectedly cut short. Maybe we will always be writing this together, indulging in memories of our co-creations but always dreaming of the next and the next and the next.

JC: I was in Perth. This is true. Sometimes overseas experiences make you want to move. Often it makes you want to move to Berlin or Brussels and makes you want to stay away forever. But sometimes you realise that Auckland, despite its geographical distance from a lot of the world, is a very special place. I love being in Auckland because I feel necessary. I feel like there is potential to affect real change in Auckland. This is probably naive. I accept this. But I think to be in the world and certainly to make work in the world, one needs to live under the illusion of purpose. Collaborating with the right people gives me purpose. And it takes so much time to find those people—don’t be in a hurry to find them.

This is why I choose to make my own work which has turned out to be mostly experimental, live art. I did it because I needed to take matters into my own hands. Cast myself in the roles I wanted to play and create narratives that empowered me to be something other than the cute little Indian girl at the end of the Jungle Book. In my live art world, I can be powerful, chaotic, sexy, dangerous, angry and the centre of plot, rather than the epilogue. My live art world is one that can make your butt clench with its refusal to play into your assumptions of who I am supposed to be or who I am about to become. The glory of this world is that it thrives in intersections and collaborations. It allowed me to attract other artists who, like me, struggle under the hurtful, ignorant eyes of the mainstream, particularly in the sexist and racist settings of theatre in Aotearoa.

Of those artists the most explosive collaboration has been with my friend, Julia Croft. We make work that is non-linear, often messy, feminist, subversive, uncertain and asks more questions than it gives answers. I like making this kind of work with Julia because I can relate to living a life that feels non-linear, often messy, feminist, subversive, uncertain and full of asking more questions than I can get the answers to. The more I live this life, the less inclined I am to find spaces or people that are linear, clean, misogynistic, mainstream, certain and sure of what the answers are. Spaces and people like this annoy me. While I can understand the attraction of feeling in control, I like feeling out of control, myself. When I experience a performance with that knife-edge quality of being uncontrolled, I feel like the outside world lines up with what’s going on inside of me. Like a rollercoaster for someone who is already on a rollercoaster.

Julia and I make work that is about finding power structures and tearing them down. The theatre is our starting point, then, the idea of us in relation to (or in conversation with) the audience. That’s what really gets us going. In our work, the theatre is the theatre, not a lounge room or bus stop although it may, at times, feel like a different world. Julia is Julia, not an 18th Century lady in a big dress running through a forest that we somehow are able to see. You, the audience exist, you are not invisible, or tucked safely behind a fourth wall or a television set, you are with us and we are experiencing the world together.

Our collaboration doesn’t exist with us individually. We work intuitively together and I’m proud of our work as an example of what an intersectional collaboration could feel like. That is to say that it is inextricably bound up and entangled in both of our bodies and timelines. It is practically and emotionally fuelled by our friendship. Practical, because we know how to live around one another having spent many years on the road touring mainstream theatre performances. Emotional because we consider each other’s friendship the primary relationship in our lives. Our art illuminates our friendship while our friendship carries our art. It is “how we pick each other up”1 and how we live.

When we began it felt the same. We were two young women fighting the patriarchy together. Over time our differences have entered into our collaboration. I am brown, she is white. I am short, she is tall. I am fat, she is skinny. At their worst, these differences hurt. At their best, they propel us in our personal political agendas to break up and take up space in the world. It is through each other that our dreams take flight further than they would individually. It is through each other that our feet are able to stay planted firmly in the realities of being different. We have co created so many images together, but the real work has been choosing to stay in the room with each other and a blood pact to never leave the other behind.

We began this piece of collaborative writing in 2019, and a version of it was published in Performance Paradigm, Vol 15, Performing Southern Feminisms in 2019. At that time I was in Auckland and Julia was in Perth and we had begun touring two of our works to Australia and Europe. I dropped Julia off at the airport in February of 2020, sending her off to London to perform our latest work, Working On My Night Moves, before she was to move to Glasgow. By March she had returned unexpectedly just before the borders closed, and we found ourselves making our way in the world through art together again. We picked up this piece of writing again in 2021 on the precipice of opening a new work, Terrapolis, another work whose life was unexpectedly cut short. Maybe we will always be writing this together, indulging in memories of our co-creations but always dreaming of the next and the next and the next.

JC: I was in Perth. This is true. Sometimes overseas experiences make you want to move. Often it makes you want to move to Berlin or Brussels and makes you want to stay away forever. But sometimes you realise that Auckland, despite its geographical distance from a lot of the world, is a very special place. I love being in Auckland because I feel necessary. I feel like there is potential to affect real change in Auckland. This is probably naive. I accept this. But I think to be in the world and certainly to make work in the world, one needs to live under the illusion of purpose. Collaborating with the right people gives me purpose. And it takes so much time to find those people—don’t be in a hurry to find them.

Power Ballad 2017

Image of Julia Croft in Power Ballad, taken by Peter Jennings, 2017

NM: We stole this vocal effects pedal from Indian Ink Theatre Company while we were doing a show with them that we hated. We took it home and started singing karaoke through it while playing around with the effects. I sang Big Spender in a Tinkerbell voice and you screamed out Because The Night in a voice called Thicker You which was just your voice but a bit thicker, a bit deeper.

When we decided to make a show about language we thought it made sense to explore what voice does in a theatre. We thought about the microphone and the power it holds and who gets to hold the microphone. We thought about what would happen if you took the microphone and found out what you could say if you weren’t really you, but you with a voice that was just a little bit thicker, a bit deeper. We laughed. A lot. And then gave birth to a demon child called Deep Talker, the angriest, most confused feminist in the world. It was a way to scream, “FEMINIST THEATRE” and “MAY THE STREETS RUN RED WITH THE BLOOD OF THE STRAIGHT WHITE MALE,” while not really having to be held to account. It’s just theatre after all, and you were just performing this thing and using a silly voice effect. But in our hearts that’s what we were screaming all of the time as we were rolling on the floor, laughing.

JC: I remember you directing the show while lying on the floor in your bra and underwear, because it was summer and the room we were working in was fucking hot. But I mostly remember that I would do things on the floor and then you would re perform them for me to see if I liked it and then I would do it back again. I think we accidentally invented a way of making work where each part of the show had been through each of our bodies so many times that you couldn’t say which part of the show belonged to either of us. I still hold this up as perhaps the ideal way in which collaboration can work. If we were more intellectual I would call it embodied collaboration.

I think splitting or disrupting the roles that have historically been subject to hierarchy within a process is a feminist act. And I read somewhere (I can’t remember where) that joy is a feminist strategy and I believe that to be true. The ways one can incorporate joy into the generating of work I now think is probably key to a successful work. I think this is especially true if one makes work from a place of anger. Which is mostly my MO. Anger gives me energy and is part of my everyday experience as a woman and making work from this place is the only way I can find to make sense of the world.

Image of Julia Croft in Power Ballad, taken by Peter Jennings, 2017

NM: We talked alot about the idea that to admit uncertainty, to admit that you don’t know seemed like a super radical thing to do. We were burnt out by processes in the mainstream, TV and theatre worlds that felt patriarchal, full of weird daddy issues. We wanted to create this gooey space where we were allowed to be floppy and as clueless in the performance as we were in our lives. But we wanted to make the statement that to be uncertain could be as strong as being certain. Like how they build big towers to sway in earthquakes, or giant structures out of bamboo. If something is rigid it's breakable. If it’s flexible it can bounce back.

We made that moment where you are lying down, after spending all your energy belting out Alone by Heart. You are lying down and you let your hair out and talk in your own voice for the first time. You say ‘I don't know’ over and over and over again. Some people must have hated that. But we loved it. It felt really free and kind of like a gentle protest. So we put a spotlight on you and after 50 performances we realised that you looked like Mr Bean in the opening credits, where he falls and goes ‘splat’ on the concrete under a floodlight. Whenever you did that part I’d perch on the seats like a vulture or something, elbows raised, ready to swoop down from some deep protective instinct over you.

Image of Julia Croft in Power Ballad, taken by Peter Jennings, 2017

NM: This was the first show I made after divorcing my straight, white, middle aged husband. I still find it incredible, that very clear obvious-to-the-point-of-cliche stance I made - divorcing the patriarchy and turning into a white haired feminist artist - an image I once described to my therapist as my vision of myself in my forties. I remember you and I feeling so sick before opening. There was so much at stake for both of us. For me it was hoping for a sign that I could do this on my own. And when it worked...I remember you standing there, mouth open, eyes closed, Pat Benatar lyrics blazing across the back wall. One voice, then two, then the whole audience singing. And you looked like you were going to cry. My hair grew whiter and my heart swelled so fucking big.

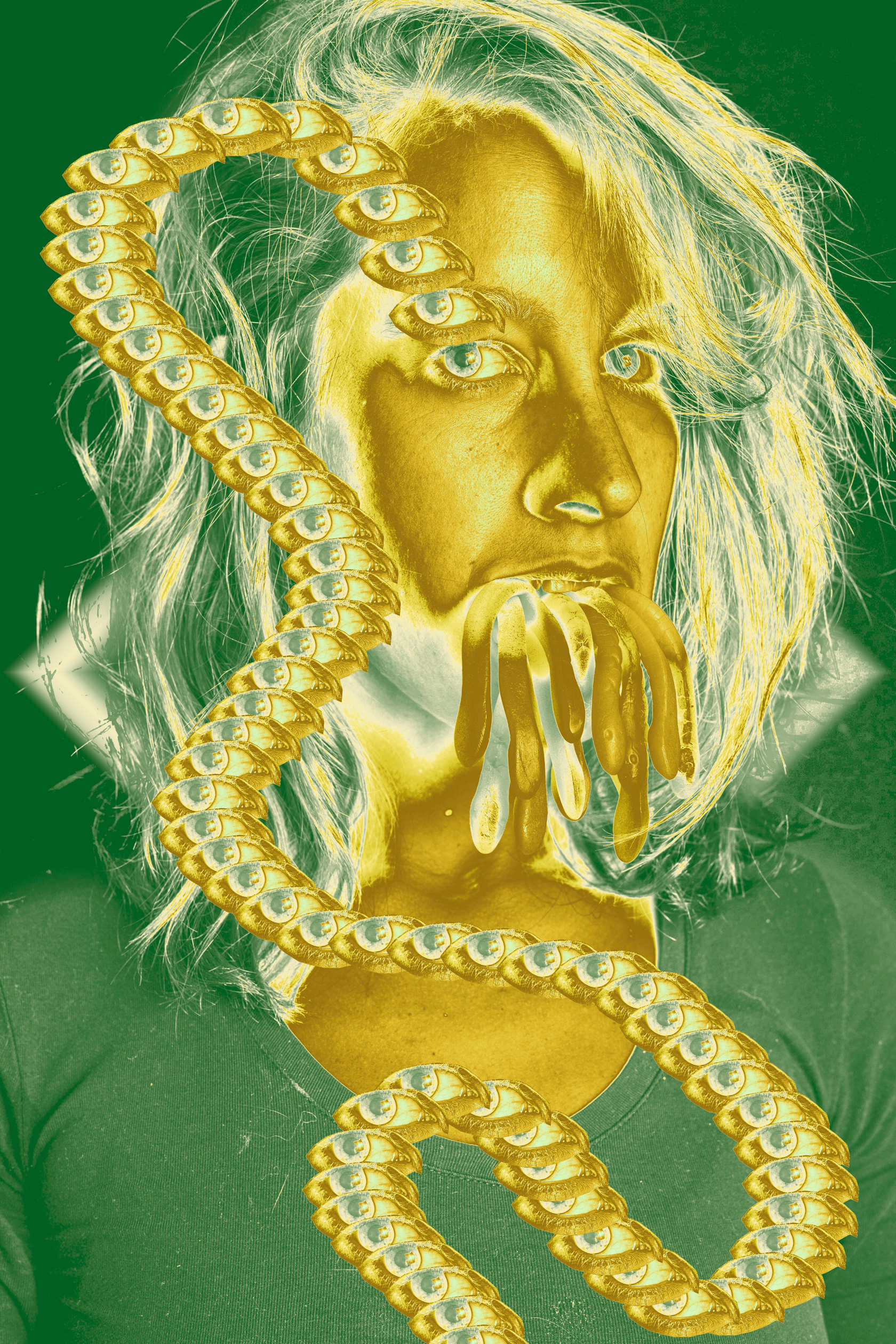

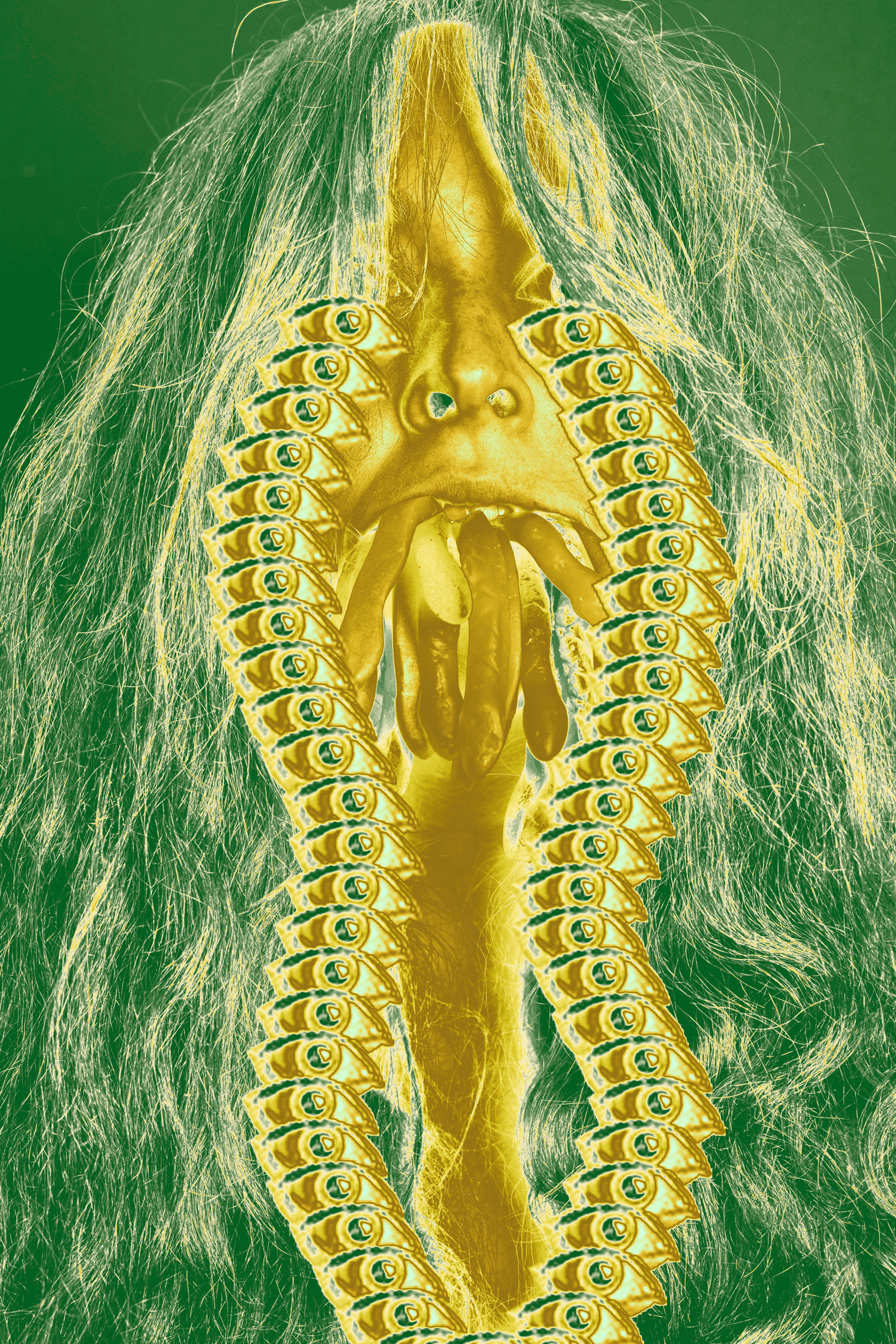

Medusa

2018

Image of Julia Croft in Medusa, taken by Andi Crown, adapted by Nisha Madhan and William Duignan, 2018

Image of Julia Croft in Medusa, taken by Andi Crown, adapted by Nisha Madhan and William Duignan, 2018

NM: We made this show with our friend Virginia. And from the start all we really wanted to do was smash apart something with sledgehammers. For a long time we thought it might be a giant block of ice. In the end it was the stage. And underneath the stage was 400 kilograms of clay and that was definitely your idea. Somehow we always mess ourselves up so that we have to have showers afterwards. I think it is because we talk about the injustices and indecencies of structural racism and sexism so much that we end up designing these extreme theatre rituals to process it. We end up having to embody the arguments then smash them up and transform them into something else and that is hard work. It’s messy, bloody, sweaty work and when we are done and we shower we feel ready to do it again. To keep trying to break it all apart. Even when things like the Christchurch Mosque shooting happens, or no one believes Dr. Blasey-Ford, and we are limp and crying in our beds, we keep trying. We feel like the only thing that could possibly make sense is to smash up the stage with a sledgehammer and pull clay out of the earth and build ourselves anew with it.

JC: Yeah sorry. The clay was 100 percent my idea. I take full credit for that. And I think it’s because I don’t really know how to talk about the oppression I feel without using metaphor. Because I think what’s exerted on the body needs to be expressed through the body. I think that this is where I started to see that the beautiful ways in which we bring ourselves to the process consciously and subconsciously are the material for the work. I feel like Nisha has a natural tendency to want to dismantle things methodically whereas I have a tendency to want to aggressively smash shit to pieces. Medusa was the meeting of these impulses. It can be measured and aggressive at the same time. Because when we tried to make it fully aggressive it felt too small. And made my anger feel small. It needed the opposite energy. And the more not-measured it got, the larger and more epic it felt. I think this work dealt with anger in a way that created space, rather than diminished it. It talked to the metaphor without representing the thing.

Image of Nisha Madhan in Medusa, taken by Andi Crown, adapted by Nisha Madhan and William Duignan, 2018

NM: There was this night that we often talk about. It was the night when something went wrong. The three microphones were supposed to descend from the ceiling, and the composer, Frances, had made a monstrously intricate, gorgon-like sound design. Each mic had its own detailed sonic dramaturgy, meticulously timed with our action and leveled to our unique ways of performing. We were standing there looking up at the grid, waiting for our mics to come down, which they did, except mine got stuck way up in the grid. We began our chant together and I stared at the mic thinking through the consequences of not having one for the rest of the show. We kept going until the first break in the text. Staring at the audience I thought, fuck it. What is the worst that can happen if I just admit that something’s wrong? I got up, marched up to the operator and asked her to get a ladder and fix it. Then you and I began this cheeky double act with the audience. We played a game of ‘maybe this was meant to happen. Maybe this is elaborately choreographed, you’ll never know will you?’ We tried so hard to one up each other you ended up stealing someone’s wine and sculling it. That is the best of us on stage together: when we can’t help sinking into joyous and naughty games with our audience.

It was the most difficult process we had run. As soon as the three of us, the three-headed-monster, left the safety of the imagined world and tried to make choices, the wheels came off entirely. There was a day in the Vault of Q Theatre where all of us just refused to go on. It was as if we had summoned the gorgon, channeled her and she came in full force, demanding us to stare directly at our bullshit and deal with it before moving on. All my past demons came in to run amuck, insecurities, regrets, deep fears. In the end the only thing that helped me was letting go of control. The process remained difficult right up to the very end. And while we are stoked with what we made, nothing beats the pride we have in our friend Virginia who, despite the emotional hardships and a severe concussion, grew her own baby gorgon throughout the process and named it Frederika. To this day she maintains that Frederika knows the sound of our voices as the chant of Medusa was the soundtrack to that first stage of growth in Ginnie’s womb.

VF: I agree with you, we went into the process beautifully and naively with this optimism around creating a feminist process which resisted the notion of a Director or Auteur who would have ultimate control of the piece. I have such special memories looking back on that first week of rehearsals. Again - rejecting traditional notions of what a rehearsal week looked like, there were no read-throughs, mapping out the show on butcher's paper from 9am - 5pm, production meetings etc. We escaped to a cottage in the bushes of West Auckland with vats of red wine, ploughmans platters and some books. We spent hours eating, drinking, lighting fires and making sculptures with melted wax. It was that gooey delicious dreaming period where anything was possible. Perhaps it was that night under the fire with the unforgettable lamb curry bubbling and the wax dripping on paper that we conjured the Gorgon herself. We had no idea of what we were up against.

I feel like I faced my biggest monster ever, as cliche as it sounds. I went head to head with my deepest fears and was forced to confront some pretty difficult stuff about myself. It truly was one of the most challenging times. I think for all of us. But every day we dragged our heels out of bed and made our way down the stairs to the dark recesses of 'The Vault' (the windowless rehearsal room at the pits of Queen St). And we battled through it. It was gruelling. Hard. Bloody. Gruesome. But then we birthed something. And it was beautiful. And I don't think it could have been any other way.

I don't want to imagine the type of show we would have made in a conventional rehearsal studio working 9am - 5pm with weekly showings and neat production meetings. This show needed screaming matches. And sweat and tears. And resistance. And power struggles. And failures. And triumphs. I will forever be grateful for this experience I shared with you both - the beautifully problematic and dangerous triangle of Gorgons. Whenever I see you both there's that magical twinkle in our eyes. That knowing and understanding of a shared birth we experienced together. That will tie us together, always.

Image of Virginia Frankovich in Medusa, taken by Andi Crown, adapted by Nisha Madhan and William Duignan, 2018

NM: I often bring up this example when I talk to people about our work because it’s not often that people admit how difficult it is to try and do something different. Theatre stories are all about how dreamy it was, how amazing the triumph of getting through it was. The story of Medusa is how we forced ourselves to stay in the room together and allowed our wider team to take care of us. Each day we would begin with a healing ritual and end by washing our hands in absolution. In the end we had an electric, funny, beautiful piece of work, a brand new gorgon baby and a friendship that runs as deep as the figure of Medusa herself. If the three headed monster is at a party together, its laughter would ring high and its gaze would cut you to the bone.

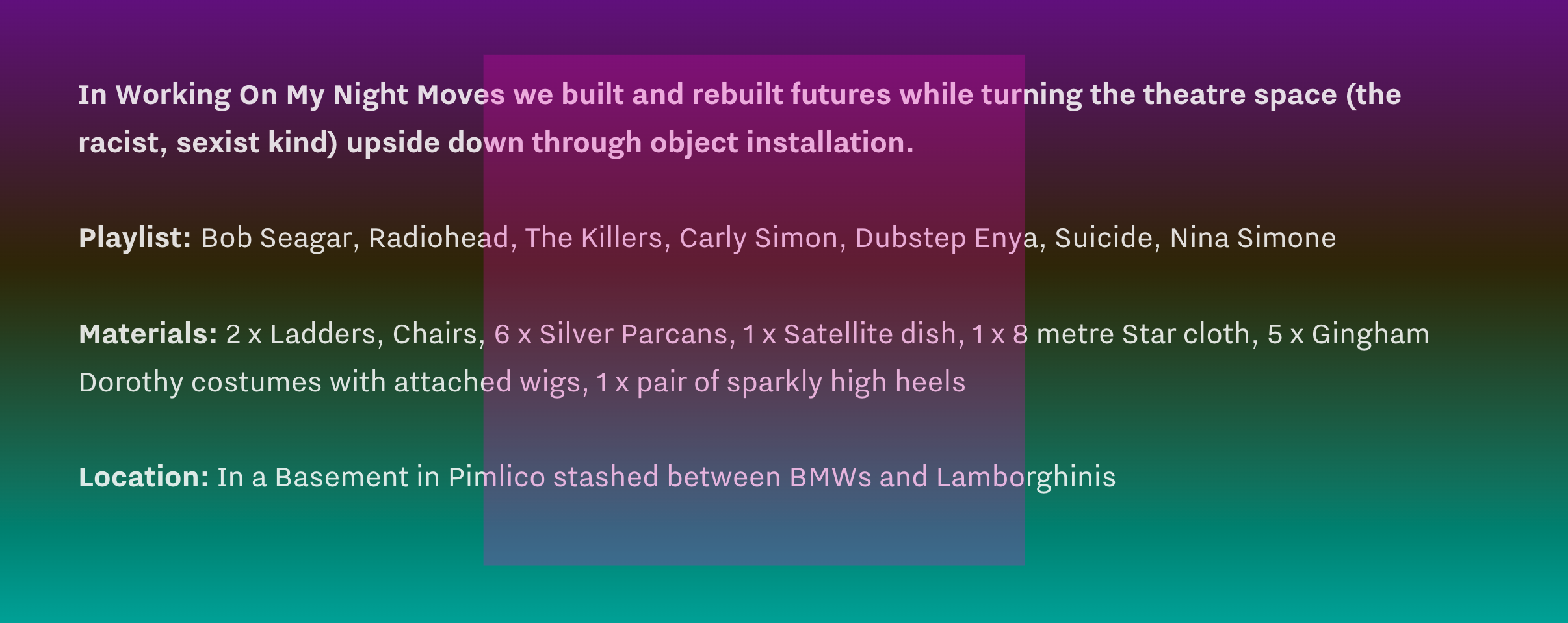

Working on My Night Moves

2019

Image of Julia Croft in Working On My Night Moves, taken by Andi Crown, 2019

NM: I remember starting with a light, just one, and swinging it around the floor. Then I remember we took a light down from the rig, just one, and we left it dangling in space. We’d never seen that before in a show. Then we hung a chair up, just one, in the roof. And I remember we played Nina Simone and projected the stars up on the roof and started crying. We always stick with the ideas that make us cry. We asked ourselves, how do we make something serene and calm and joyful, something that is free from being angry and sad at the patriarchy all the time, and more concerned with where we want to go, what future we could transition to…. So we just tried our best to get into outer space. And we decided to turn the entire room upside down. Because to ask what it would feel like to live in a world free of racism and misogyny is something like asking someone living in the sixteenth century what a life without God would be like when it’s everywhere, in everything; it’s in the screws that hold the goddamn building together. It’s almost impossible to do. But we just tried really hard to do it. And got stressed out in the process but also really, really peaceful. Really, really free.

JC: After a few years of making work that felt oppositional, making Night Moves was such a relief. Entering into a process that was finally aiming to crack an alternative way of being in the world, not continually point out what was wrong with patriarchy, but instead build our own world. Turning it upside down is just the beginning. I think breaking binaries is beyond gender and it is beyond legislation, it is actually about imaginatively cracking our conceptions of the world. Like Power Ballad the formal ideas of Night Moves were moved between both of our brains.

Image of Julia Croft in Working On My Night Moves, taken by Andi Crown, 2019

NM: I remember starting the process in residency at Battersea Arts Centre, a giant room with a knobbly wooden floor and high ceilings. Since Power Ballad, we have insisted on having key technical elements in the room. Too many times we have arrived at the theatre and allowed the technical elements, the lights and the sound to overwhelm us. Whether it’s a vocal effects pedal or a projector, we want to know how to work it, troubleshoot it so that we remain in control. We were playing around with this little birdie, swinging it around the floor and it felt like the light was dancing, but it wasn’t until we had exhausted our playlist of pop songs and went for the obvious choice, Working On My Night Move by Bob Seagar, that the whole thing just fell in place. Relaxing into an obvious choice, not trying so hard to be cool or perfectly experimental/intellectual, allowing ourselves to just enjoy a cheesy song. This is something you taught, me. Not to take oneself too seriously. Follow the fun, follow the joy, fuck what anyone else thinks.

It was unreal dragging our bespoke par cans and star curtains across the globe to Edinburgh, performing it at 10pm at night and waking up to glowing reviews by Lyn Gardner, the well loved Guardian theatre critic. We remember feeling deeply misunderstood in Auckland. Even our biggest fans felt lukewarm about it. But somehow, in Edinburgh, that noisy cluttered space of troubled artistic economies, we managed to create this island of space and calm and beauty and destruction. There was the fact that you didn’t speak the entire time. The odd way you wouldn’t even look at the audience, letting them off the hook of needing to be pleased by you. There was the calm methodical way that you would shift the room around. A smouldering ember of an energy that was determined to leave the world behind.

Image of Julia Croft in Working On My Night Moves, taken by Andi Crown, 2019

Even stranger was the feeling of leaving you and the team in Edinburgh and returning back to my job in Auckland. One morning you woke me up to tell me we had won a TOTAL Theatre award, a live art award whose lineage is peppered with many of our heroes, Forced Entertainment, Nic Green & Rosana Cade, Selina Thompson, Ontroerend Goed, Action Hero.Our minds blown and cheeks dried with tears. The next year the pandemic hit.

Something happens to us when we get away from Auckland. We relax immediately and grow bigger in ourselves. Maybe it is because our need to explain ourselves and fight for our work lessens. It’s like there’s enough space for us out there. Enough space for the work to live, liked or disliked, but brave and proud and strong in its identity. Maybe it’s pretentious. Maybe it’s just two people trying to work it out together.

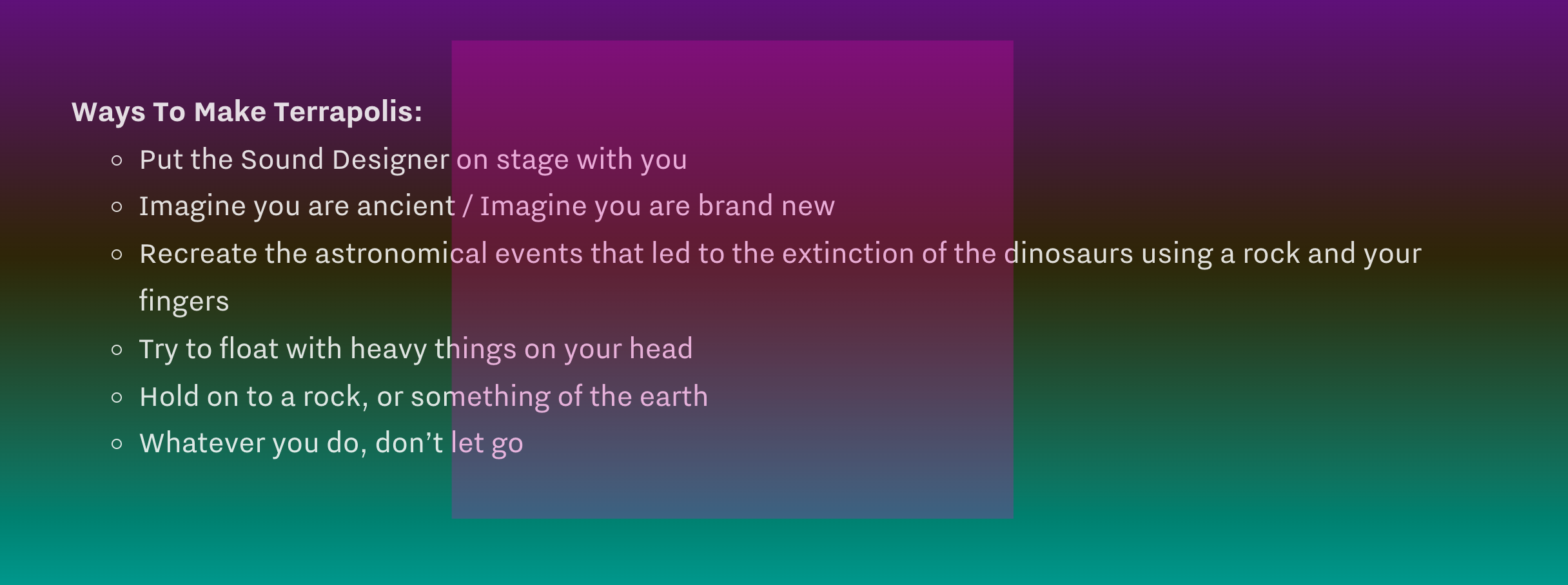

Terrapolis

2021

(interrupted)

Image of Julia Croft in rehearsal for Terrapolis, taken by Andi Crown, 2021

NM: This was the first time we have collaborated with distance in our roles. Terrapolis is very much yours, and I am the director of it. I’m the insurance you put in for yourself to make sure that what you intended was coming across. Or am I the insurance to make sure someone in the room will laugh at your jokes? We are always aware of not letting what we have together limit us or pin us down. It’s why we insist on names side by side. It means that we can leave and come back to the collaboration at any time. To do our own thing, or switch roles, or do something else like raise horses or start a food blog. Everything should be possible within this and without this. Coming into the room with you again after concentrating on my programming job at Basement was like coming home for the first time in years. My body felt like it was nuzzling into a familiar blanket on a rainy day. I knew it so well.

JC: The best part of the whole process is you laughing at my jokes. Which is partly because I am a huge big show off and you find me funnier than most, but is partly because our sense of humour is so similar that you being in the room always speaks to something in me. It helps me push things more into the absurd. It helps me take things further than I otherwise would. And we laugh. And maybe that is the whole point. And when we are old and raising horses and pickling vegetables we can look back on this chaotic time when we used to make things, and pack them in suitcases and turn up in new and exciting cities. Making eachother laugh every step of the way.

Image of Julia Croft in rehearsal for Terrapolis, taken by Andi Crown, 2021

NM: Drinking together afterwards and gassing ourselves up as we do after intense rehearsal days, we realised that this was the first process where it felt like things were working. The first time we felt truly confident in what we were doing. Confident that there are somethings we know and many things we don’t, but sharing both with an audience is how we get to move forward. When the wall came down on August 17th, halfway through our technical run, a bleak reality settled on us. We were really stuck here in New Zealand with no way out. It strikes me that Terrapolis was our first major work since the touring life of Night Moves was cut short by the pandemic. We had built our careers on the promise of space and acceptance overseas. Our work was meant to travel to havens, islands of safety, away from this one that tends to look at us with condescending head tilts. We love it here, but why is it so hard to stay here?

JC: Because I feel understood outside of Aotearoa far more than I have ever felt understood inside it. And everytime we left i would see work that would be so much better than what i was making, richer, more detailed, more cohesive, braver. And I would come home with a little fire lit under me. The travel and the works and the relationships with artist kin built off those works were the inspiration. Maybe that’s why I am thinking about horses and pickles more now. I am tired. I am sick of fighting.

Image of Julia Croft in rehearsal for Terrapolis, taken by Andi Crown, 2021

NM: We left behind our rocks, the real stars of the show, packed our designers into a car and sent them back to Pōneke. Like Night moves in Pimlico, Power Ballad in Malo Vadora, Medusa in storage, Terrapolis lies waiting for us. Artifacts, if dug up by some future archeologist, a genderfluid Indiana Jones or Sam Niell, will speak to some survival based friendship. Strange rituals with uncanny outcomes. As they piece together our particular Stonehenges, created to weave a spell of liberation from our different and similar intersections, they might feel….I don’t know.

JC: I Hope so.

1 Ahmed, S. (2019), pg 9. Living A Feminist Life. Duke University Press.